"You're different," they say, and I know they mean it as a compliment. "You don't look like..." and they trail off, not wanting to finish the sentence.

I want to ask them: different from what? Look like who?

But I already know the answers, and that's the problem.

Here's what they don't teach you about immigration: the math never adds up.

The first time I was called a terrorist was in Bonn, at the international school I attended. It was post-9/11, and I was nine years old. 9/11 was an American incident, so I couldn't understand why being Muslim in Germany was suddenly unacceptable. Yet I felt guilty - as if I had crashed the plane.

Isn't it strange how early we learn that our bodies carry histories we didn't choose?

We immigrated to Tyler, Texas when I was fourteen. I had a real American experience - high school in the South, then architecture school in Arkansas. I followed all the rules. I worked harder than I had to, smiled when people mispronounced my name, explained my heritage with the patience of a museum docent. I joined organizations, started Brown Girls Food Club (now Global Girls Food Club), let companies use me for their diversity quotas, protested for rights that weren't even for me. Hell, I even pledged a sorority (Tri-Delta—I love a side quest).

For years, I performed American-ness. I became an expert at code-switching - not just linguistically, but culturally, emotionally, politically. I optimized myself for American consumption. Because I really believed in the American dream - the America I thought we were building together.

You think that equation looks like: Time + Effort + Assimilation = Acceptance.

But if only math were that simple.

Every immigrant knows the equation: speak English without an accent, embrace individualism over community, don't talk about the old country except in ways that make Americans feel good about being American. Success is measured by how seamlessly you disappear into the mainstream.

One day you're celebrated for your "diverse perspective," the next day you're told you're taking opportunities away from "real Americans." One day your foreignness is exotic and interesting, the next day it's suspicious and threatening.

A is for Alien

The "good" immigrant narrative is seductive because it promises control.

If you follow the equation for success (work hard enough, speak English well enough, assimilate quietly enough), you'll earn your place at the table. You'll transcend your otherness through sheer force of will and good behavior.

But here's what I've learned: there is no such thing as being "good" enough.

There is no amount of achievement, no level of assimilation, no degree of palatability that will make you fully American in the eyes of people who have decided you don't belong.

The "good" immigrant myth is particularly cruel because it pits us against each other. It suggests that there are deserving immigrants (the ones who speak perfect English, who have advanced degrees, who never complain) and undeserving ones (everyone else). It's designed to make us feel special while the system that created our displacement in the first place remains unexamined.

I want to remind people that I am an immigrant. That when they dismiss me from "them," they're wrong. I am them. I am the immigrant they claim to support when they want to feel good about themselves, and I am the immigrant they fear when the conversation gets real.

I got my citizenship when I was twenty one, but before that, when we got our green card, I was surprised that the A stands for Alien. Me? An Alien?

I don't think many people know that. If you're an immigrant, you're labeled as an Alien in the US forever. Even our passport numbers have indicators that you're not from here. Even with permanent residency, even after paying taxes and voting and building a life here, the government stamps you as fundamentally other.

An alien. Like something from another planet rather than another country.

The Geography of Not Belonging

I am thirty-three years old. I have lived in America for nineteen years - more than half my life - and I am still explaining myself to strangers.

"Why is your English so good?" she asked me (mind you, this was two years ago in Brooklyn), genuine curiosity mixed with that particular brand of American obliviousness. Her excuse, when she saw my face change: "Oh sorry! It's just that my Jordanian boyfriend barely speaks English..."

I wanted to tell her that America is the only place I've lived where it's not the norm to speak multiple languages. That my mom speaks five. That English is a colonizer's tongue, and several of my countries have been subject to colonial takeovers. Instead, I sighed and walked away, because in 2023, I was tired of being a cultural translator for people who couldn't conceive of a world beyond their own experience.

The last four years, I've been splitting time between London, Texas, and lately Dubai, slowly being in the US less and less. But America was supposed to be home, and it feels like a paradox to start another life yet again in another country. Don’t I belong here now?

And I realize that the question isn't whether I belong in America. The question is whether America belongs to the version of itself that it claims to be.

The Privilege Tax

Let me be clear about something: I understand my privilege, even as an immigrant. I'm white-passing (as problematic as this term is since I look Turkic-Arab, but for context) in a country where that opens doors. My accent is "interesting" rather than "othering." My education and profession provide social capital.

Other immigrants look at me and see someone who got lucky. Americans look at me and see someone who did it "the right way." Both perspectives are true and insufficient.

But privilege in America comes with its own tax, and that tax is paid in perpetual gratitude and strategic silence.

You're expected to be grateful for opportunities that should be basic human rights. You're expected to be quiet about the contradictions you witness. You're expected to be the success story that proves the system works, even when you can see exactly how and why it fails others.

The privilege tax means you get to be the "good immigrant" example while watching the system you navigated successfully become increasingly hostile to people who share your story.

American? American’t.

What does it actually mean to be American?

Langston Hughes dreamed of an America that had never quite existed, writing "O, let America be America again— The land that" was promised but never delivered. His vision wasn't nostalgic - it was aspirational, imagining an America that could live up to its own ideals for the first time.

America was supposed to be the country that was meant for all. That was the promise that brought many families here, the dream that sustained us through visa applications and cultural navigation and the exhausting work of belonging.

But "meant for all" has always come with invisible asterisks and unspoken conditions. "It comes as a great shock around the age of five, or six, or seven, to discover that the country to which you have pledged allegiance along with everyone else has not pledged allegiance to you," as James Baldwin wrote, capturing the moment when the promise reveals itself as performance.

"You're different," they say, and for the first time, I think they might be right.

I am different.

I’m not your good immigrant.

I’m the future you fear.

Your American Nightmare,

- Ayesha

If you’d like to learn more or donate to immigrant aid, head to ACLU’s website.

Well articulated, as always, Ayesha.

Reminded me of the selected obliviousness of the people of the West. In my master’s leadership class the Professor posed a question “Do you believe in luck? Or fate? Destiny perhaps?”, of the 60 or so people in the class (including myself) only a handful raised their hands.

Me, being the only Muslim, obviously believed in Qadr so I raised my hand too.

But the professor didn’t really inquire further into our beliefs, he chose to ask those who didn’t raise their hands why they didn’t think so?

He pointed at a Dutch girl, generally quite intelligent, as to what her thoughts were- and she listed how every choice is conscious, and every result has finite possibilities bla bla. Basically, work hard and see the results.

And the Professor simply asked, “So do you think you’d be sitting here if you were born in a war torn country?”

Don’t know if it drilled into her, but lives in my head rent free 🫢

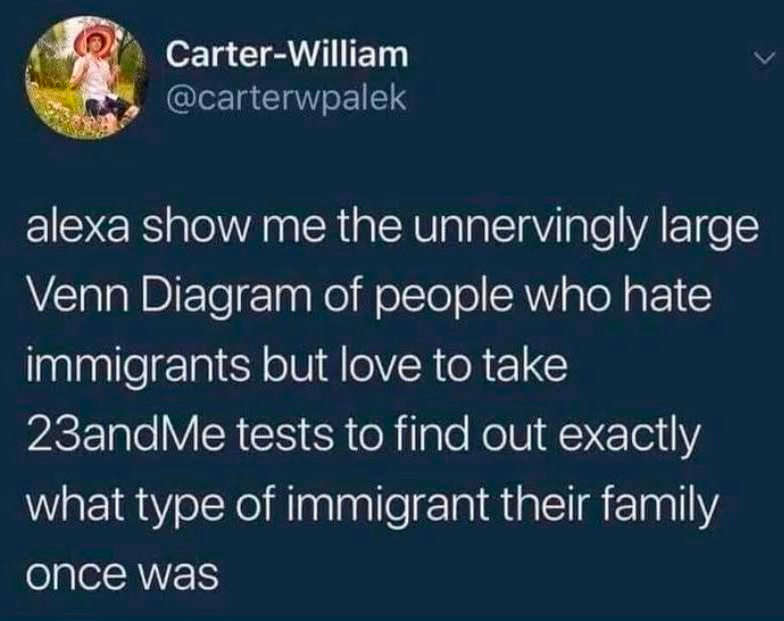

The tweet about the venn diagram of 23andme enthusiasts and people that hate immigrants is unnervingly correct.